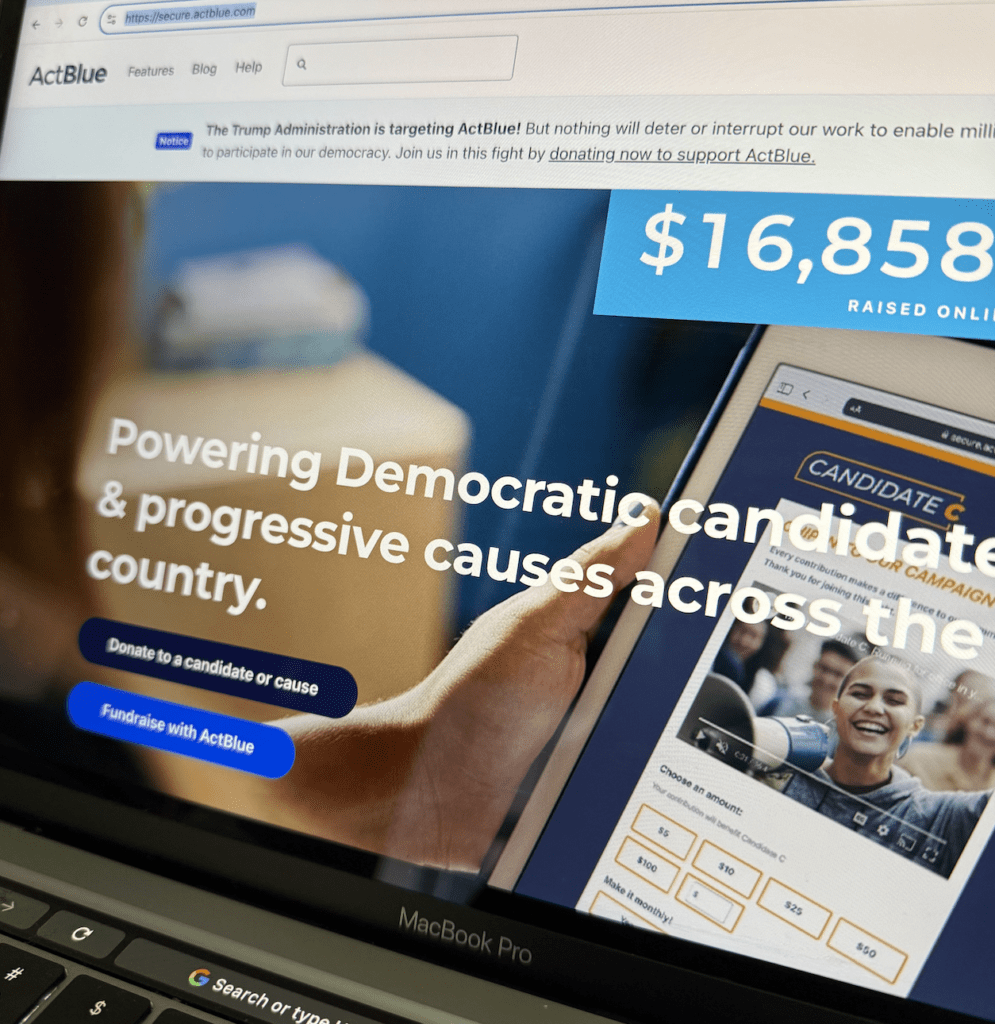

What Should Democrats Do About ActBlue and NGP VAN?

Democrats should not have been surprised when Donald Trump signed an executive order last week targeting ActBlue, the digital fundraising platform on which many campaigns and organizations on the left depend. Republicans in Congress had already asked the organization to provide internal documents under the guise of an investigation into alleged donation fraud. Trump’s EO brings the Justice Department to the party, but it’s hard to see the order as anything other than part of an ongoing campaign to cripple institutions that Republicans see as critical to Democrats’ success in future elections.

Note that Trump’s order conspicuously doesn’t include WinRed or any other Republican fundraising tools, nor does it order the Justice Department to look into fraud in platforms used by politically neutral nonprofits. Since the order practically screams “viewpoint discrimination,” I would suspect that it would be vulnerable to a First Amendment challenge. Others have pointed out that it may even amount to a “bill of attainder,” a law targeting an individual person or a defined group and a power specifically banned by the U.S. Constitution.

Regardless of whether it ultimately stands or falls, Trump’s order will still require ActBlue and its allies to spend time and money responding in court and in the media. ActBlue hardly needs more distractions right now, since the news earlier this year was of trouble inside its own office, with long-term employees resigning amid internal chaos. Democrats worried then that ActBlue might collapse on its own. Now, they have to live with the fear that Republicans could speed it to its grave.

Of course, Democrats should demand that ActBlue be held to account if it’s allowed fraudulent donations to be processed through its software. But Trump’s EO seems to really be about power, not accountability. If Republicans can knock ActBlue out of the game, they could blunt the left’s advantage in the number and enthusiasm of its grassroots small-dollar donors, a development that could particularly hurt down-ballot Dems.

ActBlue’s near-universal use among Democrats is important in itself, and it provides a classic example of a technology having a “network effect.” When most Democratic campaigns and many political organizations employ a single tool, the benefits can add up to more than the sum of their individual parts.

- Individual Democratic donors have come to know and trust ActBlue, helping them feel confident when a new campaign asks them to donate via the platform.

- Features developed for one client naturally become available to other users. In ActBlue’s case, that allows the simultaneous rollout of technologies to thousands of campaigns and organizations across the country. Likewise, staff who learn how to optimize ActBlue for one campaign can take that knowledge to their next jobs.

- ActBlue has encouraged repeat donors to enable “one-click donations” on their accounts, so that they can send money to any ActBlue campaign with a single push of a button. The system stores donors’ personal information and uses it to pre-populate donation forms with names, addresses and credit card numbers, making it easier for people to give to a new campaign at the moment, particularly on a cell phone.

Naturally, a ubiquitous technology brings weaknesses, too. As Democrats are now well aware, a single platform creates a single point of failure. If Republicans can remove ActBlue from the picture, or at least cut it down to size, they could potentially cripple Democrats’ ability to bring in money from grassroots donors, often from far outside their districts. Without access to small-dollar donations, Democrats could lose the ability to compete meaningfully except in their gerrymandered strongholds.

Similar concerns emerged this year about another Democratic digital stalwart: NGP VAN. The company’s original core technologies have helped campaigns with fiscal compliance and mass email for a couple of decades now. But, most importantly, the VAN (Voter Activation Network) side of NGP VAN has a near-monopoly on campaigns’ access to Democratic field data.

It’s not the only voter-contact software in town, but the company has long enjoyed an exclusive relationship with most of the state parties, which then provide accounts to campaigns and some organizations in their states. Campaigns across most of the country end up using VAN to access and update voter data and to create contact lists for staff and volunteers, who can once again take that expertise to their next gigs.

In February, though, the New York Times reported that Democrats almost crashed the VAN last summer, when the volume of information users were uploading and downloading threatened to overwhelm its digital plumbing. The Harris campaign and the DNC had to fund a full-time group of engineers to keep the system running through the fall, which is not exactly how a turn-key solution is supposed to work.

Behind the troubles? Perhaps one factor is that NGP VAN is a private company, not a non-profit like ActBlue, and it’s no longer run by people who are part of the Democratic movement. Many on the left suspect that the current owners haven’t invested enough in upgrades to the company’s core products, leaving the VAN vulnerable to crashes at moments when Democrats most need it. But regardless of what caused them, NGP VAN’s problems represent yet another single point of failure for Democrats. Not surprisingly, the Times story noted that an organization called the Movement Cooperative has put out an Request for Proposals for a new Democratic data system that could supplement or replace VAN.

So now the trade-offs come into play. Tech uniformity clearly brings benefits, but as in these two cases, it can also introduce the chance of failure on a catastrophic scale. What should a political movement do?

At the moment, Democratic state parties may have an incentive to maintain VAN’s monopoly, since they set the rules for access. Many charge campaigns a pretty penny for the privilege. But particularly since NGP VAN’s parent company is outside direct Democratic control, I suspect that they and the Democratic National Committee will feel pressure to allow campaigns to use alternative platforms to access and manipulate the voter-file data that state parties would still provide.

ActBlue plays a more public role in our politics than NGP VAN, and its omnipresence and its effectiveness make it a high-profile target for a direct attack like Trump’s EO. So far, other organizations in the Democratic digital world have rushed to its defense, with at least one tech provider encouraging users to stay with ActBlue but offering protection tips and backup services. I’ll also note that some Democratic campaigns and organizations have taken advantage of the moment to raise money for themselves, but unfortunately, strategic selflessness isn’t found in the arsenals of many fundraising professionals.

I hope that bad-faith attacks on ActBlue won’t survive the courts, but I also suspect that many Democrats will reconsider the idea of putting quite so many eggs in a single basket. In the end, the executive order targeting ActBlue may backfire on its authors. As veteran Democratic fundraiser Tim Tagaris wrote, “it will unleash a torrent of short-term fundraising and long-term innovation that Republicans will come to regret.”

Who knows what new Democratic organizing tools will emerge from resistance to the second Trump administration? His first term sparked a wave of innovation in Democratic grassroots tech, and troubles at ActBlue and NGP VAN paradoxically may help feed a new one in his second. Three months into Trump’s tenure, though, predicting the future seems like a fool’s game. So let’s see what happens.

Colin Delany is founder and editor of the award-winning Epolitics website and Substack, author of “How to Use the Internet to Change the World – and Win Elections,” a veteran of more than twenty-eight years in digital politics and a perpetual skeptic. See something interesting? Send him a pitch at cpd@epolitics.com.